For Europeans and a majority of people around the world, a world without livestock is not something that is widely called for. Nevertheless, a minority fraction of the European population, are considering a world that is “free from livestock production”. This clear and radical stance may seem seductive to some who consider it a coherent vision for the future. However, the singular removal of an entire food group from our future would bring with it a number of consequences that are often ignored.

Assessing all social, environmental, economic aspects related to an abandonment of the European livestock model is extremely complex even for livestock scientists and many side effects are almost impossible to predict. There are however, five clear consequences that could be considered as certain:

Europe will lose a circular bio-economy champion

In a global circular bio-economy, livestock has many valuable roles that would disappear in a world without livestock. By valorising food-chain by-products livestock contributes to a more efficient agriculture and to a rich cultural and creative society. The recycling or some say ‘upcycling’ of biomass from resources such as grass, straw and bran that are inedible for people is an important process. If not consumed by livestock, these residues and by-products could quickly become an environmental burden in themselves, as human demand for processed foods increases. The recycling of the animal’s hides or skins into leather also provides our societies with a beautiful and durable material with unique properties that serves the production of footwear, clothing, home furnishing, car seats and interiors, musical instruments, bookbinding and many more consumer products that have created and maintain cultural value of many European countries. In fact leather is probably the first circular economy product in history.

Livestock also regulate the ecological cycles, close the nutrient cycle and improve soil fertility and carbon sequestration by recycling and using manure as a bio resource and using grasslands not suitable for crops. In mixed crop and livestock areas, grasslands rotations also have the function of cutting off the cycle of crop pests allowing farmers to reduce the use of pesticides. In a world without livestock, the increased demand for plant-based production would result in an intensification of farm land use, an increase in the agricultural land needed for food production, loss in biodiversity and an abandonment of lands which are not fit for crops or protein productions like mountain regions for instance. (See also: Resource Efficiency Champions: Co-Products, an Essential Part of Animal Nutrition)

Rural Europe will be depleted

Today livestock is a key component of rural Europe. Livestock are present in almost all regions across Europe in a wide diversity of production systems according to local economic, geographical and sociological contexts. The livestock sector contributes substantially to the European economy (€168 billion annually, 45% of the total agricultural activity), to the trade balance and creates employment for almost 30 million people. Without livestock the rural exodus will increase, creating additional pressure in our cities, and a greater disconnection with nature and with our cultural heritage. Abandoned land would also result in increased forest fire risks in a context of global warming.

The use and price of synthetic fertilisers will increase

The livestock sector is not only producing food but also a wide range of by-products, starting with manures and other effluents. Today, 40% of the world’s cultivated area are using organic fertilisers coming from livestock production. A world without livestock will therefore lead to an important increase of synthetic fertilisers use. This would result in an increased dependency of European farmers on fertiliser imports, endangering our food security. Today fertilisers already represent one third of the farmer’s costs, in a future which may see a higher price for fertilisers, producing crops may no longer be profitable without a global price increase.

Fertiliser is only one symbolic example common to all types of farm animals. Many other less known by-products, such as cosmetic products, or bioenergy, from the livestock sector will be hard to replace without high environmental, economic and social cost.

European food culture heritage will partly vanish

A complete shift away from livestock production would present major challenges to meeting all populations’ nutritional needs. With no meat, cheese, eggs and fish in diets, the EU population would not receive enough of several different essential dietary nutrients from the foods they eat. A plant-only diet also would require individuals to eat more food and more daily calories to meet their nutritional needs because the available foods from plants are not as nutrient dense as foods from animals.

Eliminating livestock would increase deficiencies in calcium, vitamins A and B12 and some important fatty acids (from fish). The latter are important as they help to reduce cardiovascular disease and improve cognitive function and vision in infants. Animal food products are the only available, non-supplemental sources of some fatty acids and vitamin B12.

Against this backdrop, meat alternatives produced by a concentrated number of businesses, and the production of the B12 Vitamin by the pharmaceutical industry would replace farmers and livestock industry in rural areas.

The carbon footprint of our meals will not see a substantial decrease

From a climate change perspective, a world without livestock would likely not be as some may expect. Without ruminants, the maintenance of our pastoral meadow and hedgerow landscapes would become extremely difficult. Forests would gain ground and become more susceptible to fire in the event of extreme temperatures. A study in the US on this issue by animal scientists Mary Beth Hall and Robin R. White, considered that the total removal of livestock in the US would represent only a drop of about 2.6 per cent of total US emissions when considering the main side consequence of livestock abandonment. Considering the diversity and the difference in farming models between Europe and the US, we can only presume that the gains would be even less in Europe. In addition, there is little evaluation of the carbon footprint of synthetic meat alternatives that might not be as good as first expected[ref][/ref].

In a 2017 statement from the Animal Task Force, Jean-Louis Peyraud a researcher at INRA said, “A world without livestock farming is just a short, medium and long-term utopia. It is time for us to come back to more realistic positions based on facts. Removing livestock farming would be an absolute nonsense for humanity. But it does not mean that we do not need to improve our way of rearing animals, to respect them, to offer them a decent life and make sure that their slaughter is done without pain nor stress. We have to continue research and innovate in order to reduce the negative impacts of livestock farming and increase the services it provides to our societies.”

Sources:

- https://www.pnas.org/content/114/48/E10301.full

- https://www.futura-sciences.com/planete/actualites/rechauffement-climatique-viande-in-vitro-encore-pire-planete-vraie-75120/

- http://pr.euractiv.com/pr/world-without-livestock-farming-makes-no-sense-humanitarian-economic-ecological-and-agronomic

A first key impact of a reduction of livestock farms, will be a weakening of the rural fabric, the maintenance of our rural areas and their attractiveness. Behind every livestock farm 7 jobs are maintained in rural areas! Another major consequence of livestock reduction are the impacts on land and biodiversity.

Livestock activities are deeply rooted in European rural traditions and are present in almost all rural areas of Europe proposing a wide diversity of production systems following local and geographical contexts. The livestock sector contributes substantially to the European economy (€168 billion annually, 45% of the total agricultural activity) and creates direct jobs for 4 million people and indirectly support the work of 30 million people, mostly in rural areas. European industries linked to animal production (milk and meat processing, feed for livestock) have an annual turnover of approximately €400 billion. Future livestock production could in fact contribute greatly to the circular economy or digital industry, creating new European economic champions.

Food and livestock production is also the main contribution of rural areas to the EU trade balance. The EU is generally self-sufficient in animal products and sells on the world markets (€19.5 billion). It is a net exporter of pig meat, dairy products, poultry meat and eggs. In a more complex international environment, keeping a dynamic livestock sector is a strength benefiting not just Europe’s rural areas but indeed all of Europe, beyond the farming sector. Thanks to its export capacity, the EU is also able to promote its high standards on food safety, environment, animal health and welfare pushing its trade partners to increase their own standards.

Today almost three quarters of the European population lives in urban areas, by 2050 it is considered that 80% of Europeans will live in cities making Europe the most urbanised continental area in the world together with North America. Among the many reasons that continue to drive an exodus of rural communities to cities a clear link is observed with the higher level of income. A reduction of the livestock sector could directly increase this urbanisation trend.

Sources:

- European Urbanization Trends

Meat has been and continues to be an important food source delivering a wide range of valuable nutrients that can easily be absorbed by our bodies. Along with other animal-source foods like fish, eggs and milk it also plays an important role in several cultural traditions and recipes across Europe.

People are biologically adapted to a diet that includes meat and it plays an important role in a healthy and balanced diet. In fact, some nutrients found in meat and other animal-source foods are not always easily obtained (or even obtainable) from plant-based foods.

Meat is an excellent source of several vitamins, minerals, and essential micronutrients that can easily be absorbed by the body. A 100g portion of red meat for example will provide around 25% of the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for riboflavin, niacin, vitamins B5 and B6, and two-thirds for vitamin B12.

Diets poor in animal-source foods can lead to various nutritional deficiencies. Studies have shown that low-meat diets may pose risks for the development of the brain and reproductive system. Indeed it is recognised that animal-source foods are essential in the first 1,000 days of life for infants, and for the skeleton and brain development of pre-adolescents.

There are several important bioactive compounds in meat and processed meat products such as vitamin B1, iron, zinc, choline, L-carnitine, conjugated linoleic acid, glutathione, taurine and creatine, which have been studied for their physiological properties.

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), for example, has drawn significant attention in the last two decades for its variety of biologically beneficial effects. CLA modulates immune and inflammatory responses and improves bone mass, while carnosine possesses strong antioxidant and anti-genotoxic activities, including the anti-aging of cells.

In summary, we have developed as omnivores and meat has been a central component of our diet for millions of years. Meat and processed meat products can be safely consumed as a part of healthy and balanced diets.

Sources:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22452730

- Should dietary guidelines recommend low red meat intake?

- Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017

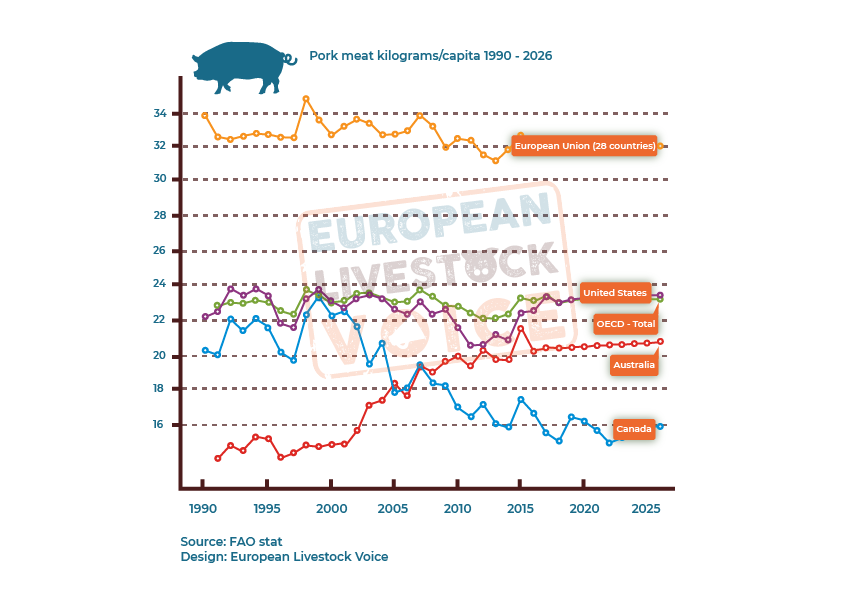

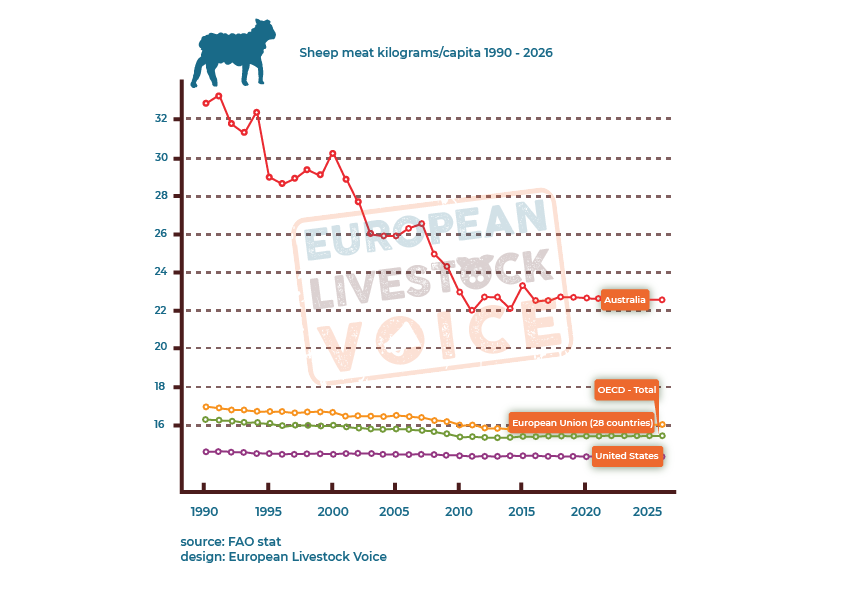

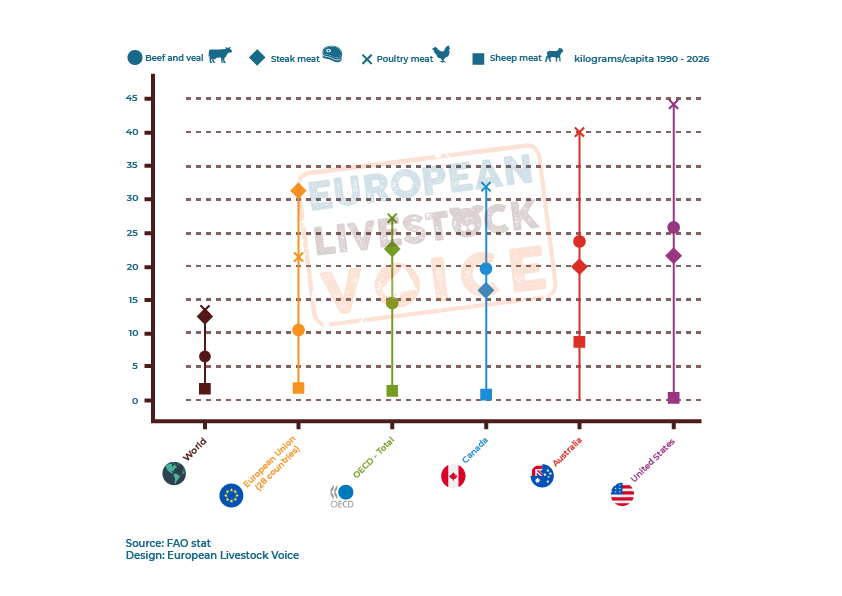

In Western countries, red meat intake has been changing and its role in society is being influenced by several factors, such as economic, environmental, ethical and health issues. In terms of kilograms/capita pork is currently the most widely consumed meat in Europe.

A downward trend in beef and veal consumption is experienced in Europe as in many other regions around the world.

See here a number of graphs from FAOSTAT with the latest trends-

No. The majority of evidence is observational and based on intakes of processed meat that exceed most European countries’ average intakes. So, all we can say if we follow science is that diets which are high in processed meats have been associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. An ‘increased risk’ does not mean that consumption of red and processed meat cause cancer as more precise studies would be required to determine this. Interestingly, a study in the UK found similar rates of bowel/colorectal cancer in vegetarians and meat-eaters suggesting that meat consumption in general isn’t a major cause of this disease.

The correlation of food, meats and cancer is very difficult to study because there are many elements, real or perceived, that may favour the onset and the development of cancer. National authorities have based recommendations on are the studies developed by the International Agency for Research Studies on Cancer (IARC) that highlight and classify the considered agents, certainly or presumably, responsible for cancer onset.

"Carcinogenic" is the term given to something that can cause cancer. The problem, in terms of communication to the public, is in the verb "to cause". It is not possible to give a determined cause-effect interpretation in this instance. In other words, it is not possible to say "if you eat processed meat THEN you will surely get colorectal cancer". In the same way it is not possible to say that if someone is exposed to a carcinogenic agent he/she will certainly get cancer. Scientists hold to the premise that "carcinogenic" is something that, taken in certain doses and for a certain period, can increase the risk to develop a certain type of cancer throughout life. However, when such information is shared with a general public, the interpretation is often that if a substance or a food is carcinogenic, this most certainly causes cancer.

Everyone has an opinion when it comes to risks and probabilities, and anecdotal evidence can be used to prove or disprove certain beliefs. And so, some people will believe that if we do not eat a specific food or something with a carcinogenic substance, then surely we are safe from cancer. Unfortunately, this is not true. We may get (and statistically it happens!) lung cancer even if we do not smoke, and a colon cancer even if we are strictly vegan. No one will ever be able to say with certainty whether, even eating processed meat every single day, we will get a colorectal cancer or not. But this does not mean that eating a certain food or not eating it would expose someone to the same risk.

Going back to the IARC report, the various agents are not classified based on how carcinogenic they are, nor does the report deal with the estimation of the risk, individual or collective, of an exposure to a given agent, once established to be carcinogenic. This means that it is not correct to treat all carcinogenic agents in the same way. Stating that "processed meat is like smoking or asbestos" is deeply wrong and certainly it pays no service to the public opinion. Carcinogenic agents are different, but it is not the IARC's task to classify this aspect. There is also an interesting point to note regarding the consumption amounts investigated by the IARC, which are 50 grams of processed meat or 100 of red meat per day. This level of consumption is much higher than the level of European consumers and, in general, of the rest of the world.

Consumers, like most people confronted with decisions, have different reactions, so the information provided by sources of authority are very important and should be advised over non-science-based sources. Some may can decide to continue eating a food because the increased risk is small. Others may decide to reduce their consumption. The most important thing for authorities to keep in mind is to communicate any potential risk in a clear and proper way.

Sources:

- Cancer in British vegetarians - Keys T et al. (2014) Am J Clin Nutr 100(suppl): 378S–85S.

There is no objective reason to equate processing de facto with unhealthiness. It is true that some specific aspects of food processing may indeed be detrimental to health, for example by generating trans fatty acids or reducing the micronutrient availability, but this is mostly of little concern in the case of fermented meats like ham, salami, and sausages.

The word “processing” is defined by the Oxford dictionary as to “perform a series of mechanical or chemical operations on (something) to change or preserve it”. Some processing steps are harmless or may even be beneficial, for instance to allow for preservation or to enhance the bioavailability of micronutrients or other beneficial compounds. Binary oppositions as “processed/natural”, of which one term is more highly valued than the other, have been exposed by post-structural theory as mere cultural constructs rather than foundational categories we can confidently rely on.

Furthermore, some of the ingredients used to produce meat products have sensory, technological, and especially hygienic safety advantages which is mostly neglected, whereas their potential negative impacts are overstated. For instance, nitrate in fermented meats leads to colour and flavour development as well as enhanced food safety, while these fractions are very small compared to the intake through drinking water or vegetables.

Sources:

- Gibney et al., 2017

- Cornwell et al., 2018; King and White, 1999

- Ribas-Agustí et al., 2017; Weaver et al., 2014

The practice of adding substances to foods for easy storage is not a chemical or industrial invention, it is an ancient tradition. The use of salt was and still is a way to preserve meat and inhibit the growth of bacteria.

Examples of adding substances to food include: the addition of an acid juice (such as lemon) to prevent the blackening of a vegetable; the use of the smoke from wood especially ones rich in resin; and, in the specific case of the meat, the use of salt. The ancient Romans observed that saltpetre improved the production of cured meats and sausages, avoiding the browning of the meat and especially preventing the proliferation of unwanted bacteria.

Precisely for this reason, in the production of some cured meats, nitrates and nitrites are added in controlled quantities, as they have the property of maintaining the colour of meat.

In 2003, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) explicitly stated in a scientific opinion to the European Commission that “in most processed meat products the addition of nitrite (or nitrate) is necessary to prevent the development and production of toxins for C. botulinum”.

Thanks to the use of the refrigerator and microbiological knowledge, in addition to compliance with hygiene rules and to the exploitation of the bacteriostatic properties of spices and herbs such as garlic, pepper and chilli, you can nowadays produce safe cured meat using few preservatives.

In the PDO hams like Parma ham (PDO = Protected Designation of Origin), for example, the prolonged maturing process makes the use of nitrates unnecessary, which in fact are no longer used in these products. As for all substances, also in the case of these compounds an excess consumption can lead to negative consequences for health.

Although it should be noted that nitrates are a component of many plant foods (lettuce contains 3 grams per kg), the nutritional balance is the way to valorise the benefits of each individual food reducing health risks.

Sources:

- EFSA: Re‐evaluation of potassium nitrite (E 249) and sodium nitrite (E 250) as food additives

Consumption of meat or so-called ‘meat substitutes’ is a matter of personal choice, but it is important that the consumer is well-informed of the properties and production methods, etc. before making that choice. In terms of environmental impact however, based on currently available data, in vitro production offers no environmental advantage compared to real meat.

In general, it would be wise in the EU to assess the risks for human health before promoting this type of production as a better alternative to livestock farming.

Producing meat without animals is a long-standing desire for some people. Churchill in the 1930s was already thinking about a future with cultured meat. However the reality behind the utopia is not necessarily what Churchill would have expected.

Lab-grown meat, cultured meat, in vitro meat (IVM), are all different expressions that started gaining popularity in 2013, after the production and tasting of the world’s first ‘burger’ made from stem cells by Mark Post from Utrecht University. Cultured meat has since then been presented in general media as one of the most promising alternative ‘meat’ sources to solve both animal welfare and food safety issues, while preserving the environment. This alternative to conventional meat has attracted huge investments, especially from well-known digital-tech companies that are now betting on a fast market uptake of these products at the expense of traditional livestock production. However, when looking at academic publications, the scientific community seems more skeptical when compared with the general media about the development of in vitro meat..

In Vitro meat is not magic meat, it still needs to be produced!

Cultured meat, or in vitro meat, is meat derived from tissue and cells grown in a laboratory setting rather than in a living organism according to the definition given by Mark Post. In factual terms, In Vitro meat is a cluster of muscle cells taken from an animal that multiply in petri dishes with a culture medium rich enough to allow the cells to multiply. Today, even with the most advanced techniques, culture mediums still need either hormones, growth factors, foetal calf serum, antibiotics or fungicides to allow for cell development. Against this background in vitro meat cannot be considered as a “natural” alternative to EU livestock which has to respect strict standards on the use of antibiotics and prevents the use of hormones. As a matter of fact, such products cannot even be called “meat”, as some important cell types (e.g. nerves, adipocytes, etc..) are not part of this invention which is just a cell culture.

In Vitro cell cultures, an environmental impact that remains controversial

It is not yet clear whether cultured meat production would provide a more climatically sustainable alternative. The climate impacts of cultured meat production will depend on what level of decarbonized energy generation can be achieved, and the specific environmental footprints of production. There is a need for detailed and transparent LCA of real cultured meat production systems. Based on currently available data, cultured production offers no environmental advantage compared to real meat[ref][/ref].

The fact that lab-meat is an energy-consuming process and involves the use of compounds and molecules normally not allowed for feeding animals (hormones, antibiotics, etc.) is very often ignored.

Consumer acceptance

Researchers believe that artificial meat can be high in protein, but there is still a big concern about the iron and vitamin B12 content. Aside from nutrition, one of the challenges for cultured meat is to mimic traditional meat in terms of sensory quality/taste at an affordable price in order to become acceptable for future consumers. If companies engaged in the development of lab grown meat expect to be competitive by 2020 replicating the actual complexity of meat structure and taste will remain challenging as well as convincing the great majority of consumers. In this context, irrelevant of individual perceptions, in vitro meat cannot be considered as a short-term alternative as it will have to first face the long and challenging process of consumer acceptance.

Sources:

- Hocquette et al., 2013

- Cultured meat timeline

- Cultured meat in western media: The disproportionate coverage of vegetarian reactions, demographic realities, and implications for cultured meat marketing

- Bill Gates and Richard Branson are betting lab-grown meat might be the food of the future

- https://www.futura-sciences.com/planete/actualites/rechauffement-climatique-viande-in-vitro-encore-pire-planete-vraie-75120/

- Is it possible to save the environment and satisfy consumers with artificial meat?

- What is artificial meat and what does it mean for the future of the meat industry?

- Climate Impacts of Cultured Meat and Beef Cattle - John Lynch and Raymond Pierre Humbert

- Lab meat is cheap enough for anyone to buy

- Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: A systematic review