Claims that livestock production has intensified in Europe over the past decade are grossly generalising the path of development in farming practices as many different trends can be observed across Europe, depending on the type of livestock production and what we actually refer to when we refer to “intensification”

So what does ‘intensive’ mean in terms of agriculture?

“Intensive farming” is a term used in public debates about certain farming practices. It often implies farms with large numbers of animals and practices that maximise production output, while minimising production costs. It is also often indicated as being responsible for the bulk of environmental impacts from livestock production and biodiversity losses. However when you consider the scientific debate, the concept of intensification is not that straight forward[ref]Agricultural intensification: definition and controversies as regards biodiversity and food security https://biodiv2014.sciencesconf.org/47410/document[/ref]. So before engaging in conversations on livestock intensification, it is important to understand what intensification actually means.

This can encompass any number of things: from intensive land use; intensive use of chemical inputs or farm machinery; intensive labour use; intensive use of technologies; use of feed and water resources; and the list goes on…

These different factors have different impacts on the environment, on biodiversity and on the social framework. In this direction, hydroponic systems or urban farming seen as positive in general media are advanced examples of intensive farming systems. At the opposite end, traditional farm system are also working with concepts like “sustainable or ecological intensification” with high ecological intensity, aiming to use natural processes and ecosystem services in an efficient way.

The merits and challenges of different farming practices including the practices classed as intensive are in reality very complex and, in the case of Europe, more diverse.

“Livestock intensification” is not a systematic trend in livestock production in Europe

If we consider the basics of what can be classed as “intensification”, i.e. an increase in farm input intensity (including use of fertilisers, pesticides and purchased feed), can we observe a clear trend towards an intensification of livestock in Europe?

Let’s take a look at the statistics...

Eurostat[ref]https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Agri-environmental_indicator_-_intensification_-_extensification[/ref], the European public agency for statistics, developed a methodology[ref]Purchased feed cost is divided by the feed price index in the country in the same year. This allows to develop a method where inflation and input prices fluctuation are deducted.[/ref] that could give first answers to this question. Farm input intensity was used as a proxy of agricultural intensification and was defined as the level of inputs used by a farm per unit of factor of production (in general land).Between 2004-2013[ref]Commission Regulation (EC) No 1242/2008 of 8 December 2008 establishing a Community typology for agricultural holdings https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32008R1242[/ref], the share of agricultural area managed by high intensity farms[ref]Higher expenditure than a 350 constant EUR/ha[/ref] kept a stable trend in the EU-28, except for the mixed livestock holdings (grazing and granivores) which increased by 8%.

For the EU – 28, the share of agricultural area managed by medium intensity farms[ref]Expenditure between 350 and 155 constant EUR/ha[/ref] for granivore holdings decreased by 4%, whereas the share of mixed livestock fluctuated around the 25% mark. For grazing livestock there was a steady decrease of 5%.

For the EU – 28, the share of agricultural area managed by low intensity farms, increased in the case of granivore holdings and decreased by 3-4% in the case of mixed livestock holdings. The grazing holdings share increased, showing a tendency towards extensification.

Any livestock farmer will tell you that animal welfare comes top of their agenda, especially on larger farms for the simple reason that without happy, well-looked after animals, you cannot make a living from livestock farming. So, like with any business, making money is important but livestock intensification is not about skipping over the basics.

The main goal of any farmer is to generate an income while producing high quality products that are market-conform. And livestock farming in Europe includes a wide diversity of practices and production methods. So why is it that one term, “intensive farming” is so often used to portray a very negative picture of farming?

The livestock sector has for some time tried to develop a more neutral terminology that could apply to modern, resource-efficient production models. But there will always be difficulties with trying to move beyond the buzz words, especially in media reporting terms.

But no matter the terminology or practices involved, every livestock farm in Europe is subject to strict rules that include animal welfare under theEuropean Convention for the Protection of Animals kept for Farming Purposes.

Healthy farms go hand-in-hand with healthy well-cared for animals

Farming practices that are considered intensive are an advanced way of farming where, among others, animal health and welfare related issues, the responsible use of animal genetic resources, sustainable animal nutrition and feeding are closely monitored. Keeping animals in good health, based on improved genetic selection, balanced feed and advanced monitoring tools will also maximise farmers’ incomes. In this context, what is good for animals is also good for farmers.

Keeping food prices affordable for everyone

Modern farming models have adapted from the development of modern societies, and the greater efficiencies created allow for a level of production based on large amounts of food for all society. The many different types of farming practices in Europe together provide populations with a regular supply of safe and affordable milk, meat, fish and eggs.

In addition, further processing of meat offers the opportunity to add value, reduce prices, improve food safety and extend the shelf-life. New techniques of food processing, packaging and preservation are continuously being developed to meet with societal demands. This can result in increased household income and improved nutrition[ref]http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/themes/en/meat/home.html[/ref].

Europe presents a great diversity of production from one region to another, so average sizes are difficult to define. What is known for sure is that family farming has always been a cornerstone of agricultural activity in the EU, and when compared to third countries, European farm sizes remain relatively small.

In the EU smaller farms (in economic terms) practice a range of different activities with mixed cropping, mixed livestock, or mixed crop and livestock farming simultaneously conducted. These mixed systems are part of our cultural heritage, and this makes it hard to establish a precise definition of what is the average size of dairy, beef or poultry farms.

Comparison of farm size, financial resources, labour force, or number of animals per farms should be considered cautiously. As statistics on the smallest farm are hard to establish due to mixed systems, public data mostly comes from specialised farms in the top 10 European producing countries.

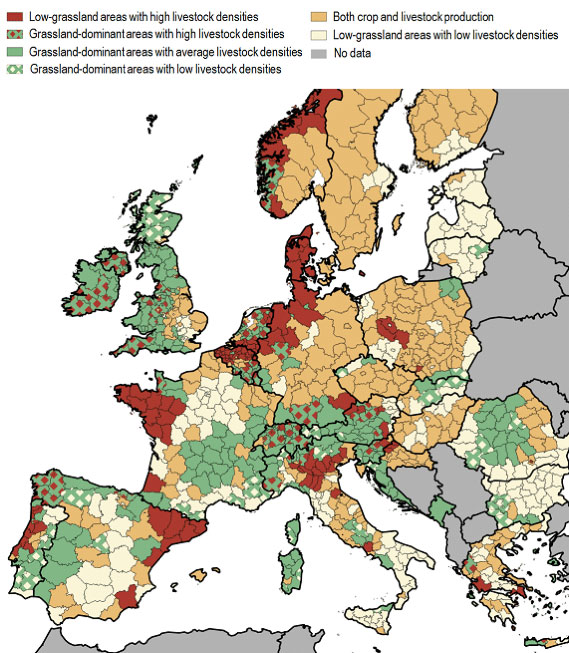

When considering the type of livestock production on a European map, a limited number of regions can be considered as having a clear specialisation.

Figure 3. Typology of European livestock production areas (Source: INRA based on Eurostat, 2010)[ref]A collective scientific assessment of the roles, impacts, and services associated with livestock production systems in Europe - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Typology-of-European-livestock-production-areas-Source-INRA-based-on-Eurostat-2010_fig3_317825615 [accessed 30 Jul, 2019][/ref]

The average size for livestock farms in Europe is below 50 hectares and hosts less than 50 “livestock units”

The “average European livestock farm” uses 34 hectares of agricultural land area and has a herd size of 47 livestock units[ref]http://animaltaskforce.eu/Portals/0/ATF/Downloads/Facts%20and%20figures%20sustainable%20and%20competitive%20livestock%20sector%20in%20EU_FINAL.pdf[/ref]. Even in livestock driven regions, a farm in the European top-10 countries uses 51 ha of land (about 35 football fields), with around 2 people working on the farm, hosting 79 “livestock units”[ref]https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Livestock_unit_(LSU)[/ref] for a total value produced of 138,000 Euros. This first set of statistics from Eurostat shows that we are far from the image most commonly portrayed that the European farming sector is a mass of “factory farms” even in the most specialised and productive countries! European Farms, even in the specialised producing countries, farms remain small when compared to third countries.

Among the specialized farms, those oriented in sheep farming are the largest in terms of surface with about 90 ha, but the smallest in terms of livestock units with an average of 61 and operating capital (less than 113,000 Euros).

Meat-producing farms tend to employ less labour in top production countries in Europe. On the contrary, granivores employ the most manpower (more than 2 people). They also own the largest herds with 312 livestock units, and mobilise the most capital (more than 280,000 Euros). Specialised dairy farms have the second largest herds with about 76 livestock units, mobilise the second highest capital (231,000 Euros) and the second highest level of employment with 1.9 people.

Important differences exist in Livestock “farm size” across Europe

All livestock sectors combined, the United Kingdom, Denmark and France host the largest farms in terms of surface, with roughly 95 ha per farm. Poland, Italy and the Netherlands have the smallest farms, with less than 40 ha per farm, with as low an average as 18 ha in Poland.

Clearly farm size and mobilised capital have no direct link in Europe. Dutch farms are among the smallest according to the farm size criteria but are among the largest in terms of livestock and working capital, along with Danish farmers. In fact, in terms of mobilised capital, Denmark, Netherlands and Belgium are the top 3 countries, far ahead of Germany, the United Kingdom and France for example.

The livestock sector does not receive direct subsidies per kg of meat produced. The sector receives subsidies only indirectly, through direct subsidies that are granted to farmers in the form of a basic income support based on the number of hectares farmed.

There is actually no direct link between livestock production and EU subsidies. The direct payments of the CAP are linked to the land, meaning that you have to justify a certain amount of farmland to receive subsidies. If you take production of pork or poultry for example, these livestock systems do not necessarily require farmland and therefore those sectors are not directly subsidised.

Milk or cattle production is different, as pasture land or land for fodder are necessary and these receive direct subsidies. Those pasture lands are very often placed in zones where it is not possible to grow crops so this contributes to the maintenance of the landscape.

Some interest groups believe that indirectly, the livestock sector is massively subsidised through the amounts received by crop producers, knowing these crops will be used for feeding the animals[ref]https://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/issues/nature-food/1803/feeding-problem-dangerous-intensification-animal-farming/[/ref]. This is forgetting that an important part of the ration (especially for non-ruminant) is soybean which is only produced in the EU in relatively small quantity and is therefore imported from North or South America. In addition, an important part of these crops fed to animals are by-products (oilseeds) as the main element of the crop is used for human consumption (e.g. when you grow sunflowers, you use the oil for human consumption and the by-products are used to feed animals). Therefore, using the argument that livestock production is largely subsidised for the production of feed is denying that most of these crops are firstly used for human consumption and that animals are just eating the by-products that would otherwise be wasted if not consumed by those animals.

The European Union is indeed importing significant and growing quantities of meat into the EU. Poultry meat is by far the main import sector, with more than 800,000 tonnes imported every year. In bilateral free-trade negotiations, the EU has tried to include provisions for topics such as animal welfare in the negotiations. However, very often these provisions require collaboration between the parties meaning no binding rules.

There was a peak in 2016 with more than 900,000 tonnes that was imported. Imports are coming mainly from Brazil (45%), Thailand (30%) and Ukraine (15%) and concern high value cuts, primarily breast meat, that are preferred by EU consumers and that are produced at a much lower cost in these countries.

The second most imported meat in the EU is beef meat, with annual amount reaching around 340 000 tonnes. Here again, Brazil is the main supplier (40%), followed by Argentina (20%), Uruguay (15%) and USA-Australia (10%). Similarly to poultry, mainly high value cuts are imported into the EU, meaning that the competition from third countries has an even higher economic impact on EU producers. 180,000 tonnes is imported of sheep/goat meat every year, which is quite significant related to total EU production, as imports equal 20% of the EU production. Imports are mainly coming from New Zealand and Australia.

Imports for pork are relatively small as they amount 33,000 tonnes every year with Switzerland representing 60% of this amount.

When it comes to animal welfare, imports from third countries are only subject to their national legislation.

Welfare is not recognised in WTO rules making it impossible for countries from the EU, with high animal welfare standards to impose identical standards on the imported products. Therefore, for as long as animal welfare are not recognised at WTO level, there is no guarantee that meat or live animals imported from third countries have respected the exact same standards as the ones imposed on EU producers.

In many of the countries we are importing from the legislation is limited.

In bilateral free-trade negotiations, the EU has started to try to include animal welfare provisions in the negotiations. However, very often these provisions require collaboration between the parties meaning no binding rules. Nevertheless, in the case of poultry meat for example, the legislation on the protection of animals at the time of killing has to be implemented by the third country in an “equivalent way”. And in the egg sector the Commission is trying to embed the respect of the ban of conventional battery cage in trade agreements, which is in application in the EU since 2012. Against this background, EU farmers, cooperatives and their organisations are promoting high animal welfare standards at world level and try to work together with EU stakeholders to push trading partners to respect higher health and welfare standards.

Slaughterhouses in Europe have to abide by rules set out in EU law such as the regulation on the protection of animals at the time of killing.

The slaughterhouse has a crucial position in the meat chain. At the slaughterhouse, the work of the farmer stops and the processing stage to consumer begins. Virtually everything in a slaughterhouse revolves around animal welfare, hygiene, food safety and control, both from the cattle and then from the meat.

Upon arrival at a slaughterhouse, the animals are first examined for health and well-being by a veterinarian. This is the ante mortem inspection (AM). Animals that are sick or unable to walk should not be slaughtered and used for human consumption. The medical officer issues a slaughter permit for each healthy animal.

And there are many other strict processes in the slaughterhouse operations, including:

Animal welfare officers

According to the Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 of 24 September 2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing,in the slaughterhouse ' animal welfare officers ' ensure that the animals are treated with care. The officers provide advice on improvement opportunities where necessary. These officers are present at the unloading, driving, stunning and killing of the animals. They also monitor welfare in the temporary reception area.

Unloading and stunning measures

The slaughterhouse takes measures to prevent animals from becoming stressed. For example, pigs go to a stable on arrival where they can relax, the unloading itself shall not be done in a manner stressing the animal. Slaughtering must respect EU rules preventing stress and suffering as much as possible. Before the animals are slaughtered, they are first stunned,after which they are cut in the neck and bleed out. Slaughter of animals is a profession for which you must have a special education.

Approved plants

Animals may only be slaughtered in an approved slaughter location.The company must comply with (construction) requirements in the area of the accommodation and transport of the animals, food safety, hygiene, the environment, animal welfare, animal health and the storage and removal of the residual and by-products from slaughter. Slaughterhouses that do not meet the requirements run the risk of having to close their business. This also applies to companies that endanger food safety and public health.

Butchers and slaughter

The slaughter process is surrounded by administrative rules. Partly for that reason, there are very few butchers who slaughter themselves. Slaughtering an animal is also labour-intensive work. Almost all butchers buy a carcass, parts of a carcass or boned parts or meat from a meat wholesaler and then they process that into the meat products and / or sausage and meat products that they sell in their butcher's shop.

Meat inspection

After the animal is slaughtered, a check is carried out on the carcass, on organs such as the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys and lymph nodes. An approved carcass is stamped. The carcasses are sold to meat processing companies at home and abroad. Rejected carcasses are destroyed.

Quartering the carcass

The liver, spleen and kidneys belong to the parts of a slaughtered animal called the fifth quarter. The other 'quarters' are the longitudinal carcass. By-products that are counted up to the fifth quarter are the blood, skin, lower part of the limbs, head, tongue, brain, bones, other organs of the abdominal cavity (tripe / gastrointestinal tract) and chest cavity (heart, lungs, the 'thymus' at the calf).

Testing the meat

Judges who check the carcass can read from the organs whether there are abnormalities. When in doubt, the organ is further examined in a laboratory. In addition, blood samples are taken for testing to ensure that only approved meat comes into circulation.

Residues screening

Meat cannot contain remnants or residues of a medicine. Animals treated with medicines may only be presented for slaughter after a mandatory waiting period to prevent residual veterinary medicinal products from remaining. This is checked to make sure withdrawal periods and maximum residue levels are respected.

(See questions under animal health for more info)

Food chain inspection

The Food Chain Information is used for the meat inspection. It contains information about the livestock farm, where the animal comes from. It provides information on the health status of the company's herd, and on which farms the animal was before it came to the slaughterhouse.

The Food Chain Information also contains information about the use of veterinary medicines and other analysis data on food safety and public health. Results of meat inspections from previous slaughtering of that company can be found there, as well as the name of the responsible veterinarian.

Classification

An inspection report is drawn up for each carcass. Every approved carcass is obliged to weigh shortly after slaughter and receives a quality assessment based on a general classification system. We look at the fleshiness, the fatness and the meat colour. The conformation of calves is indicated by one of the letters EUROP. For adult cattle, that is SEUROP. The fatness and meat colour are indicated with a number. In pigs, conformation is indicated by AA, A, B and C.

Quality control

The NVWA checks whether companies have their records in order, so that measures can be taken if something is wrong with a product and there are risks to public health. The NVWA assesses the performance of the quality systems. It is examined whether procedures are effective enough for food safety. Inspectors also look at whether a company can take adequate corrective and preventive measures. Certifying organizations check whether the slaughterhouse works according to the requirements of the certificates. At slaughterhouses and meat-processing companies that export outside the EU, veterinarians and inspectors from those exporting countries often look at quality assurance.

Hygiene practices

Hygiene is very important during the slaughter process.The slaughterhouse takes precautionary measures, such as protective clothing for those who want to go into the slaughter room, compulsory disinfection of footwear and mandatory disinfecting hands with soap after every break or after visiting the toilet. In addition, there are rules for slaughtering itself. The intestines and organs are removed in such a way that the carcass is touched as little as possible. Storage and transport from the slaughterhouse is subject to hygiene rules. Only employees who slaughter may enter the slaughter room. The hygiene protocols are laid down in the company's Hygiene Code. Every employee must adhere to it. Everything is focused on clean slaughter.

- Knives and machines

Knives used for slaughter are regularly disinfected during slaughter to prevent any bacteriological contamination of carcasses. The storage of knives is bound by hygiene rules. Machines and slaughter rooms are cleaned and disinfected at least daily. This also applies to the trucks that transport meat. - Slaughter line stops

Bacteriological research is being carried out at the slaughter line to rule out possible contamination. Systematic checks on cleaning and compliance with hygiene rules also include checks on the quality of the water used in production. At a slaughterhouse that does not work according to hygiene rules, the inspector can temporarily stop the slaughter line. The company must first disinfect the slaughter line or the slaughter room before further work can be carried out. - Protective clothing

Slaughterhouse employees wear hair nets, helmets, ear plugs and overalls with a rubber apron and boots or footwear with steel toe caps. The latter depends on the type of work they do. Jewellery, piercings and makeup are forbidden. Employees who work with knives wear a protective glove made of stainless-steel links to help prevent accidents.

Risk prevention

Some parts of an animal's body are destroyed as a precaution because they may pose a risk to public health. This is the case with BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy). Eating products with a BSE infection can have health consequences. Parts of an adult bovine animal that pose a risk may under no circumstances be processed into food for humans and animals. Brain and the spinal cord of a slaughtered adult bovine are so-called Specific Risk Material (SRM) that must be burned. Disposal is mandatory by law. The risk material includes the spleen, the skull, the tonsils and the colon that are destroyed as 'animal waste'. The SRM rules apply to adult cattle, but also to ruminants such as sheep and goats.

Disposal

The law makes a distinction between Low Risk Material (LRM), High Risk Material (HRM) and Specific Risk Material (SRM). LRM consists of meat products whose expiry date has expired or whose meat structure differs.

Slaughterhouses and the circular economy

Slaughterhouses play an important role in the circular economy. Almost all animal parts rejected as human food products are used for many other purposes:

Specialist processors

Residual and by-products from the slaughterhouse go to specialized companies for further processing and valorisation in a different sector than the food or feed chain. The cattle hide and calf skin, as well as the skins of other animals (sheep, goats, pigs, rabbits, etc.), become leather for all kinds of applications.

The intestines are processed into strings for musical instruments and tennis rackets but are also used as sausage casing.

Brushes and brushes are made from a by-product such as pig bristles. The pig's bladder is suitable for covering lampshades. The bones provide raw material for glue, gelatine and buttons. Animal fat is a raw material for the oil and fat industry (soap). Animal fat is suitable for the production of biodiesel.

Other parts of the animal are raw materials for pet food or for the pharmaceutical and / or cosmetic industry. Everything is usable.

Water and energy

A slaughterhouse uses a lot of water. Not only because animals have to be cared for on arrival, but especially because slaughter rooms and machines are frequently sprayed and disinfected.

The companies have taken measures to reduce water consumption. This can be achieved by collecting used water and making it suitable for cleaning commercial vehicles and stables. Water used in the slaughterhouse ('process water') contains meat proteins, fats, blood residues and carbohydrates. This water is first purified and disinfected. This also happens with waste water that goes to the sewer system. Slaughterhouses save water with saving spray nozzles and by reducing the water pressure when cleaning with a high-pressure sprayer. Water consumption is also limited by the use of evaporative condensers on cooling machines and by limiting the rinsing frequency and rinsing time.

Energy (electricity, fuel) is required for the cooling of carcasses and the transport of livestock and meat.Freezing meat for longer storage costs a lot of energy. Slaughterhouses take all kinds of measures to limit the consumption of water and energy, but also to reduce the use of mineral fuel in order to reduce CO2 emissions.

To use energy more efficiently, slaughterhouses have invested in energy-efficient equipment and in alternative energy sources, such as solar and wind energy and biogas. The manure for these biogas plants comes from the stalls where animals for slaughter are temporarily collected. The biogas is used as fuel for the trucks. This is especially possible for larger slaughterhouses. Furthermore, investments are being made in the construction of cogeneration installations. These 'CHPs' use gas to generate electricity and, at the same time, to heat water for the disinfection of business premises and the heating of buildings. Energy saving is finally achieved with new cooling and freezing techniques.