Animal welfare is an important concept. Many Europeans are concerned about the welfare of both farm and companion animals and it is an aspect in livestock farming that is often called into question. Views on animal welfare are very personal and the concept is much more complex than it seems at first sight. Ask 3 people what “animal welfare” means and you will most probably get 4 different answers – and this is perfectly understandable! This is why it is interesting to look at what science says about it.

Animal welfare – A challenging concept for science

Today, all livestock professionals in Europe are subject to legislation based on knowledge derived from animal welfare research. Livestock professionals, as with any other sector, need to rely on a stable and predictable framework. So, it is still important to try to find a definition, relying on the scientific progress, which is the case for this evolved definition developed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE):

“Animal welfare means how an animal is coping with the conditions in which it lives. An animal is in a good state of welfare if (as indicated by scientific evidence) it is healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, able to express innate behaviour, and if it is not suffering from unpleasant states such as pain, fear, and distress. Good animal welfare requires disease prevention and veterinary treatment, appropriate shelter, management, nutrition, humane handling and humane slaughter/killing. Animal welfare refers to the state of the animal; the treatment that an animal receives is covered by other terms such as animal care, animal husbandry, and humane treatment.”

A first general scientific consensus was first found in the Committee’s FiveFreedoms from 1965, and this remains a strong scientific reference point still today.

The Five Freedoms approach is for example the basis of the European Commission’s Welfare Quality project. As the largest ever animal welfare research project in Europe, Welfare Quality sets out to design principles for animal welfare assessment.

The critical point in both of these, as well as other scientific approaches to animal welfare is that as a starting point they take the animal’s point of view. Before the 1960s, concepts such as animal health were mostly used and focused on human perception of visible pain and suffering of animal, offering a limited but more straight forward approach to the issue, especially for farmers. In fact, as animals can’t express feeling directly, the definition and the evaluation of animal welfare greatly depended on the outcome of science based evaluation. With the progress made in neuroscience for instance, the base of knowledge that we have continues to grow, and therefore defining what “animal welfare” is will not conclude at a limited end-point, but will continue to be debated and developed.

Animal welfare –A challenging ethical concept

Animal welfare is a subjective concept, therefore there is a value component to animal welfare which cannot be explained by science alone. Ethical concerns over animal welfare can be grouped in three main types:

- Basic health and functioning- animals should be well fed and housed, free from injury and disease, and relatively free from the adverse consequences of stress.

- Affective states of animals- animals should be relatively free from negative states, including pain, fear, discomfort and distress, and capable of experiencing positive emotional states.

- Natural Living- animals should be able to carry out normal patterns of behaviour, particularly behaviours they are highly motivated to undertake, in an environment that is well suited to the species.

Most animal welfare scientists agree that these 3 aspects are all important. There is less consensus on where we should draw a line in the gradient within an aspect. For example, to what level can we impose short-term pains or keep social animals in isolation for longer term health benefits. Also the balance between economic versus animal welfare considerations is an area of further discussion.

In debates about the welfare of animals, people tend to emphasize different concerns, in part because opinions about the appropriate course of action are rooted in human values. Some emphasize elements such as freedom from disease and injury. Others emphasize the experience of positive emotions and the avoidance of pain. Others again emphasize the ability of animals to live reasonably natural lives by carrying out behaviour similar to their ‘wild’ counterparts and having natural elements in their environment. These concerns make up different criteria that people use to assess animal welfare.

There are substantial overlaps of course. An animal with a disease may experience pain, while on the other hand good health is a good starting point for positive emotions. Likewise, natural behaviour may lead to positive emotions. Good animal welfare may contain elements from all three dimensions, while a single-minded pursuit of one criterion may lead to poor animal welfare.

Taking one concrete example, most animal welfare lobby groups argue in favour of free-range housing systems. For farmers, veterinarians and researchers this is a single-minded approach, because free range housing, in spite of its qualities, can also lead to increased disease pressure, higher mortality and sometimes also negative emotional states, for example in hierarchical animal herds.

This is why animal welfare debates are often more complex than they seem.

Sources:

- INRA MAGAZINE • N°2 • OCTOBRE 2007

- https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:18162/FULLTEXT01.pdf

The concepts of animal welfare and animal health can often be confused and are sometimes interchanged in conversations. Today, there is wide consensus that although these are two distinct concepts, they are inherently linked with each other.

Animal health is a prerequisite for animal welfare. As with people,any kind of illness can mean pain, discomfort, loss of appetite, etc. meaning that people, or in this case, animals do not feel ‘well’. Likewise, when animals, like people, are stressed, not well-fed or cared for, then disease can strike. So there is an inherent link between the two concepts.

Farmers in Europe are well aware that in the instance of disease occurrence, it is important to seek veterinary care so that the appropriate treatment can be advised to avoid animal suffering and uphold good standards of welfare.

If the welfare of animals is poor, when they don’t feel well or they feel stressed, there is increased susceptibility to disease and aggressive behaviour. This is not in the interest of the farmer, so in general the farmer will take appropriate measures to ensure good animal welfare.

This intertwined relation between the health and welfare of animals makes both concepts extremely important in livestock farming. And in practice they are of equal importance, not only for the animals themselves, but also in a broader societal context because animal health and welfare are both important aspects of food safety and meat quality, as well as public expectation.

Some people argue that a transition to higher numbers on animals on farms compromises animal welfare, saying the sheer number of animals makes it impossible to provide individual care and attention. However, no direct links, positive or negative, between farm size and animal welfare, have been confirmed in studies specifically examining this.

There is no evidence that farmers on large farms view the welfare of animals differently than farmers on small farms. Depending on considerations of what welfare entails, smaller farms are more likely to accommodate outdoor access, and some people value this aspect when considering animal welfare, but there is no evidence to support lesser welfare standards from indoor housing.

What can be established about larger farms is that such production systems are more likely to implement science-based, standard operating procedures, to provide training for their employees, and to utilise technology to track and monitor animals and to implement costly changes to improve welfare.

A 2016 study ‘Farm Size and Animal Welfare’[ref]Frazer et al (2016), “Farm Size and Animal Welfare”, Journal of Animal Science[/ref] proposes that policy and advocacy efforts aimed at reversing increases in farm size would be better directed toward improving welfare on farms of all sizes.

Animals get sick because they are kept in cramped conditions in factory farming systems! - is this factual?

Animals get sick from time to time, just as people do, but there is no explicit link between animal diseases and the farm setting.

Strict EU and national control measures with strong biosecurity guidelines are generally in place to uphold animal health. And Europe’s farm-to-fork monitoring system includes key policies for animal health management, which is supported by a wide availability of preventive solutions, like vaccines, or diagnostics for early detection, as well as therapeutic treatments. No matter the farm size or practice, good animal health is on the whole reliant on sound farm management, and continued cooperation between the relevant stakeholders in Europe.

Each system has its merits and its challenges. For example, contrary to some beliefs, free range animal housing systems can present some challenges, which can of course be overcome through increased vigilance and reinforced biosecurity measures. Overall, there is general consensus that no matter the holdings, healthier herds mean better yields, so it is always in the farmer’s interest to ensure the good health and welfare of their animals.

Sources:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5607874/

Natural behaviour, one of the elements identified in the Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare, is an increasingly polarising question when it comes to farm animal welfare. Contrary to what may appear logical to some, what is natural may not always be good for welfare.

Polarised conversations on the use of cages in farming often focus on the debate as to whether farms should fit with the animals, or the other way around. On one side of the debate is the position held by animal lobby groups, who believe animal welfare can only be upheld in free-range housing systems, as only free-range housing systems can accommodate natural behaviours.

While natural behaviour clearly has importance for animal welfare, it is however disturbing to boil something as complex as animal welfare down to simplistic concepts such as - “free-range is good, confinement is bad”. We must not forget that natural behaviours for animals include such instincts as expressing dominance. The hierarchical nature of egg-laying hens is for example the direct reason why the mortality rate is twice as high in free-range housing systems compared to enriched cages. For the animal who is free to be pecked at by dominant animals in the herd, a free-range housing system will not necessarily help with ensuring good animal welfare.

This serves as an example of why simplistic approaches to animal welfare, perhaps based on our own human thoughts and feelings, may actually decrease rather than improve levels of animal welfare on the whole.

What is ‘natural’ is not necessarily ‘good’ in animal welfare terms, and free-range systems are not best per definition, just because the word ‘free’ resonates in such a powerful way with almost everyone, as world leading animal welfare scientist Marian Stamp Dawkins puts it. Instead, she says, our guidance to good animal welfare goes through the knowledge animal welfare research can provide us:

“Do captive animals want to do all the things their wild counterparts do, or do they find plentiful food without having to hunt for it preferable? The connection between ‘natural’ and ‘good’ welfare becomes something that has to be established with facts by looking at the animals themselves, not just by making romantic assumptions about what life in the wild might be like.”[ref]Marian S. Dawkins (2012), Why Animals Matter, Oxford University Press[/ref]

Through so-called choice tests, in which animals’ motivation for different resources are measured through the workload they are willing to put up with to get access to the resource, can provide very good scientific knowledge on the preferences of animals. Such tests have documented the high importance of dust baths for hens, and nest building for mink, both behaviours found in the domesticated species’ wild counterparts. The same kind of tests however, have documented that access to swimming water is not particularly important to the farmed mink, demonstrating that to the extent in which you can ask the animals themselves, natural behaviours can both be important and not important. Whether they are is a matter of science, not emotion.

The use of cages or other confinement techniques in farming is a hot topic in Europe today and it is an emotionally-charged debate. Some groups seek to establish animal confinement as ‘bad’ for animal welfare, and free-range housing systems as ‘good’ for animal welfare – but in the real world how animal welfare is achieved or upheld is not so black and white.

If we take farrowing crates for sows as an example, these may look uncomfortable to us as people, but they are actually designed to protect the piglet. The temporary confinement in the crates prevents the sow from lying on the piglets by accident which may otherwise naturally occur, leading to the death of the piglet(s).

Conversations around the use of cages, free movement and around the right for animals to have their own life, will likely continue to focus on very personal human views and values. While these values are legitimate, they do not offer any objective thinking around the definition of animal welfare based on species-specific, farm-system specific and scientific knowledge.

The question of confinement is covered by some species-specific EU legislation. An EU directive from 2007 also lays down minimum rules for the protection of chickens kept for meat production[ref]Council Directive 2007/43/CE(June 2007)[/ref]. It aims to reduce the overcrowding of chicken holdings by setting a maximum stocking density and ensure better animal welfare by specifying requirements such as lighting, litter, feeding, and ventilation. Another example is the European Waterfowl sector has changed all its equipment in response to the Recommendation of 22 June 1999 of the Council of Europe. All individual cages – épinettes- have been replaced by collective cages that allow ducks and geese to stand with a normal posture, turn around without difficulty, flap their wings and carry out normal feeding and drinking movements. This housing system meets animal welfare requirements, sanitary imperatives and the ergonomics of the farmer's work while achieving excellence in production.

How is animal stress managed in livestock production ? What measures can be considered to reduce stress?

Animals can experience stress for a number of reasons: fatigue or injury; hunger, thirst or temperature control; environment; unfamiliar people, handling, environment or surroundings; etc. Efficient, experienced and calm handling of livestock, using recommended techniques and facilities, as well as taking measures to eliminate pain and accidental injury, will reduce stress in the animals

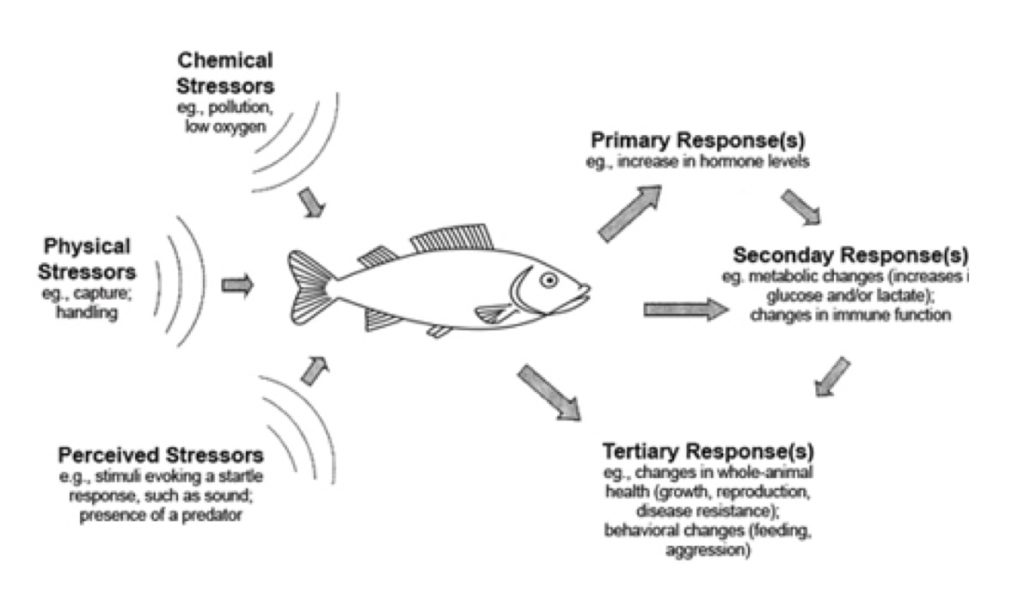

Stress is a physical or mental factor that causes tension to the body and/or mind of both people and animals. Stress is a reaction that initiates, usually, the “fight or flight” response, composed by both endocrine and neurologic factors (adrenaline and noradrenaline). Stress provoking factors may come from the outside (the environment and psychological or social situations) of the body or from the inside (illnesses, medical procedures…).

Each individual responds to stress in a different way. For animals, the response to stress may depend on their species, breeds and life conditions.

Animal stress can have different causes

The stress response includes several changes that may have negative effects on livestock. These effects include changes in the immune function and increased susceptibility to disease, decreased feed intake and rumination, inhibition of oxytocin release and reduced fertility, among others. These factors not only impact on the animal’s welfare but also on the productivity of a farm. On both levels it is in farmers interest to assess and anticipate animal stress and manage it appropriately.

There are a number of phases inherent to the farm animal’s life which may represent a stressful moment, e.g. transition phases, like weaning, can be a delicate period for a piglet for instance; or giving birth and lactation for nursing sows, who will need supplements of energy to better care for their newborns. Other common stressful situations for domestic animals include, health care procedures, among others. Stress induced by handling agitates and excites animals, which increases body temperature and heart rate, raises corticoid levels in their blood (adrenaline) and reduces immune functions, leaving the animal more susceptible to diseases. Animals accustomed since their birth to human proximity will have a less intense physiologic response than animals that have been raised in a pasture with little human contact.

Environmental stress has an impact on livestock too. All animals perform better at their “thermal comfort” zone, which varies among species. This kind of stress may be managed by providing adequate nutrition and hydration in each case, with proper management practices (shelters, ventilation, etc.) and health care when needed.

Solutions

Avoiding handling the animals as much as possible would be almost the perfect solution in every developed farm. That is why in some places around the world, farmers have begun to implement some advanced measures as far as finances allow: for instance, with automated milking robots, cows enter whenever they want and there are no pressures for them to be herded through the farm in order to be milked!

Apart from facilities and general shelter, nutrition also plays an important role; therefore, nutritional strategies can help animals to cope with eventual challenges coming from their surroundings, improving their welfare.

For instance, to avoid loss of appetite and therefore undernutrition of newborn piglets, farmers will choose flavourings to increase the palatability of the diet after lactation and then stimulate the animals’ appetite.

Feed additives in particular may be important also in maintaining footpad/hoof health. Together with animal health care these contribute to stronger joints and support the immune system of animals by maintaining gut health, resulting in increased resilience to stressors and infectious diseases.

Giving high caloric feeds in winter to animals may help to cope with low temperatures along with an adequate heating system for the enclosures and the avoidance of cold air flows. On the other hand, providing low caloric feed in summer can help to tackle the effect of high temperatures, avoiding the fact that the animal may generate more body heat itself; this should be accompanied by adequate shaded areas around the enclosures, an adequate ventilation in the indoor facilities and the availability of fresh water sources in different formats –drinking water in the case of cattle; showers for pigs.

Also for cattle and dairy cows, one thing that seems to help them de-stress are brushes to scratch their backs! Who doesn’t like a nice back massage?

Animal farming is cruel! Animals should have equal rights to humans! - what lies behind these claims?

This is another hot topic and an emotionally-charged issue for many people, and understandably so. Equating a love of animals and a desire to continue consuming animal-sourced food may cause a moral dilemma for some. But labelling farming practices as cruel in general, would be a sweeping generalisation of an overall well-managed livestock production in Europe which takes care of the health and welfare of the animals as they move through the production system.

It is no coincidence that the world’s first animal protection law was passed in the British Parliament in 1822. At the time British moral philosopher Jeremy Bentham, the founding father of utilitarianism, was a prominent figure in British society. Bentham’s utilitarianism states that the moral right action is the one that produces the best outcome for the greatest number of individuals – and this includes animals. The best outcome is calculated as the total amount of pleasure or happiness minus the total amount of pain or suffering.

While Bentham’s powerful idea paved the way to today’s welfare-focused societies, it is also the philosophical foundation of animal welfare. The idea that farm animals should not suffer from for example stress, fear, disease, or injuries has been a well-established guideline at least since the 1960s. Since then the concept of animal welfare has developed in a direction demanding not only avoidance of suffering, but also the presence of positive emotions, e.g.European Commission’s Welfare Quality.

Animal welfare research eliminates animal suffering

Any claim that animal farming is cruel is directly related to the notion of animals suffering. Suffering may occur on animal farms on rare occasions, but it is in no way the norm in Europe. Acts of animal cruelty may be due to poor management or lack of training and should always be signalled to the appropriate authorities.

With proven scientific methods animal welfare researchers are indeed well equipped to establish whether animals suffer or not, and much modern animal welfare research focuses on enrichment designed to increase the positive emotional state of farm animals. Such science-based knowledge is and will continue to be developed and reflected in the modern housing systems for farm animals. These housing systems are designed for animals to have an overall positive experience of their own life – if animals were generally suffering such housing systems would simply not be allowed.

Balancing pain and pleasure quickly becomes a personal matter

An important critique of Bentham’s utilitarianism is how we are supposed to calculate the outcome of our actions in measures of ‘suffering’ and ‘happiness’. Obviously such calculations can quickly become a matter of personal opinion and interpretation.

We can argue in favour of animal farming in terms of the jobs it creates, the families it supports, the necessity of animal protein in our diets, the creative diversity of chefs and designers, food supply security and many other things which contribute to human welfare. But some people will argue that these benefits do not outweigh any kind of suffering on individual animals, and just as it is impossible to have traffic without traffic accidents, there can be no animal farming without animals occasionally in distress. As such the ‘zero pain’ position is legitimate, but of course it exists among other legitimate positions in our free society with its diverse values.

Whether animal farming is cruel or not ultimately comes down to personal values and interpretation of suffering. It is however difficult, if not impossible, to find any life – human or non-human – which has not been exposed to some pain at some point. It is standard in modern farming to treat animals in distress as quickly as possible, and if we can accept this, animal farming can hardly be deemed cruel.

Sources:

- EU Welfare Quality Network

- Brambell 1965 reference

Some more radical interest groups promote the idea that meat is murder. This is a clever use of emotive language to persuade people that the practice of raising and indeed slaughtering animals for food – a practice that is socially accepted and advised from a dietary and nutrient perspective since around 300,000 BC – into something that is negative.

In a philosophical sense this idea is based on a notion of life being morally ‘sacred’ regardless if it is a human or an animal life. In extension of this advocates argue that animals are entitled to freedom rights similar to those of humans, notably the right to their own life. To most people however, eating meat is the most natural thing in the world. There is a good reason for this intuition too. It is currently the dominating theory within natural sciences that consumption of processed animal protein has been a crucial element in the evolution of mankind. Studies show that it would have been biologically impossible for humans to evolve such a large brain as the human brain without meat, and to that end the conclusion is we owe humanity itself to the consumption of animal protein. Quite simply, humans are omnivores by evolutionary design.

A comprehensive study has shown 84% of vegetarians eventually go back to eating meat, some 30% of those saying they experienced specific health-related symptoms while on a no-meat diet. While some people cope fine with a meat-free diet, others clearly do not, and on this backdrop it seems rather out of order to claim meat is murder.

In addition to meat eating being somewhat embedded in the human DNA, there are a number of other problems associated with the idea of “meat is murder”. If life itself is universally sacred, are trees and plants also in the scope of moral concern then? Are insects? Where do we draw the line, and why do we draw it there? The next problem arises when considering all the wild animals which inevitably are dying in the fields while humans cultivate crops for plant-based diets, just as there are questions about important medicine which can only be developed through animal experimentation, or pest control which amongst many other benefits prevent the spreading of diseases.

While meat is murder may be a captivating slogan, the universal freedom rights are exactly based on the idea that humans are capable of understanding the concept of freedom, hereunder the freedom to express your thoughts and ideas. Thus, meat may be murder to a tiny number of people in this world. To most people meatis simply a part of a healthy, balanced diet as well as a legacy from our human evolutionary history. What is not natural nor acceptable in regards of mankind evolution is the current and generalised food waste of such precious resources. Farmers are well aware and often the first to engage in the fight against food waste.

Sources:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5417583/

- https://time.com/4252373/meat-eating-veganism-evolution/

- https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/99legacy/6-14-1999a.html

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/diagnosis-diet/201903/the-brain-needs-animal-fat

Within the European Union, regional production of meat is not equal to regional consumption, and this is one of the underlying reasons for transport of live animals between Member States.

Live animals may be transported for fattening or for slaughtering purposes, the main reasons are due to:

- In the case of fattening: because some countries are relatively advanced in selective performant breeding (i.e. France for bovines, Denmark for pigs) and others are specialised in fattening either in feed production (i.e. Spain)

- In the case of slaughtering: sometimes it is for religious reasons (Halal = Muslim tradition, Kosher = Jewish tradition) or just because of the live animals market demand.

But there are other reasons why live animals are transported across and sometimes out of Europe.

For breeding purposes

Animal breeders help to improve certain traits in farm animals to improve animal health and welfare while ensuring a better use of resources to contribute to the sustainability of the livestock sector. This means developing and maintaining a large variety of genetic resources. In order to do this in a best risk-managed way, the facilities for animal breeding are located in different regions and countries. These different facilities in different countries help to ensure the best genetics for each type of farm, from organic to other modern farms, at an affordable rate, without any compromise on the animal. If a facility experiences a disease outbreak, the genetic resources still remain safe in other places of Europe, or even in third countries. This is why the transport of live animals is sometimes needed, as it’s not always possible to only transport semen or embryos. And breeders impose standards to ensure the transport is carried out in the best conditions, because the final purpose is to have well-cared for, high-value animals.

Farming is about livelihood, and farmers along with animal breeders do their best to ensure application of EU transport regulations, and improving animal transport is important for a healthy European livestock sector.

EU Regulations on animal transport

Transport of live animals is a topic of contention in Europe, in particular during hotter periods and there are specific EU rules to define the allowed means of transport and the 'fit to travel' status. Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005 of 22 December 2004 on the protection of animals during transport and related operationsprovides prescriptions about: travel time, rest times, load factor and quality of the means of transport. In addition, slaughterhouses have additional requirements. For example, animals may only be transported in a certified means of transport. The animals must also be healthy in order to be classed as 'fit to travel'.

In view of the possible spread of infectious animal diseases, inspectors also check compliance with the rules for cleaning and disinfecting lorries.

Transport and temperature

In the Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005 several measures are stipulated to ensure adequate ventilation, temperature:

- Ventilation systems on means of transport by road shall be designed, constructed and maintained in such way that, at any time during the journey, whether the means of transport is stationary or moving, they are capable of maintaining a range of temperatures from 5 oC to 30 oC within the means of transport, for all animals, with a +/- 5 oC tolerance, depending on the outside temperature.

- The ventilation system must be capable of ensuring even distribution throughout with a minimum airflow of nominal capacity of 60 m3/h/KN of payload. It must be capable of operating for at least 4 hours, independently of the vehicle engine.

- Means of transport by road must be fitted with a temperature monitoring system as well as with a means of recording such data. Sensors must be located in the parts of the lorry which, depending on its design characteristics, are most likely to experience the worst climatic conditions. Temperature recordings obtained in such manner shall be dated and made available to the competent authority upon request.

- of transport by road must be fitted with a warning system in order to alert the driver when the temperature in the compartments where animals are located reaches the maximum or the minimum limit.

In the EU food market, different food labelling schemes co-exist with the aim of informing customers and providing trust on different quality characteristics of food products. There is no European food label as regards animal welfare but some countries like Germany, Denmark and the UK have example of such labelling.

Many consumers value labelling schemes that are regulated by EU law (e.g. organic products, PDO indication, nutritional fact panel). Labelling is an important cue for consumers as it helps to quickly communicate information about a product or production process. In policy-making, the consumption of specially labelled products and its role in improving the welfare of livestock, has attracted considerable attention.

Are all the labels the same?

The majority of local and national experimentations on animal welfare labelling tend to be binary, indicating whether a product was produced using animal welfare friendly standards or not. Yet, there are many intermediate qualities that binary labels could not portray, turning those experiments into market failure and no-go zone for many farmers. In this regard, multi-level label experimentations seem more promising at they may show different process standards of products in an explicit way. Further tests need to be conducted to evaluate consumers reactions and understandings of those systems.

On the other hand, many quality labels that are already well-established take already into account animal welfare standards in their specifications on issues such as transportation or slaughter conditions.

What would be the objective of an EU animal welfare label?

From the examples already existing in the EU market in some member States like Germany, the objective of the animal welfare label would be to inform the consumer about which products are above the legal standards. With pork products for example, Germany has a label which considers the conditions of the facilities where the piglets are born, the lactation duration, if they are castrated and how, the farmer’s training on animal welfare, transportation to the slaughterhouse, methods and welfare in these facilities, and how they go further from the legal standard requirements. In Denmark, on the other hand, they developed a “hearts” scoring system in 2017, from one to three depending on the level of animal welfare applied to pork production. In 2018, the Danish authorities released a report where they have found only 4 cases of infringement after inspecting 66 farms. The requirements to get more than one heart on your label depends, mainly, on space available for the animals or the conditions of production (outdoor production and maximum 8 hours of transportation).

Why is there no EU level label on animal welfare?

Firstly, because the harmonised risk indicators on animal welfare for the EU are still being developed by the European Commission and, secondly, because there is no common definition at EU level on what “animal welfare” means and implies in terms of practices. The European livestock sector is engaged in all debates around this issue in order to get clear definitions while taking into account the many different factors.

Sources:

- Special Eurobarometer 442, December 2015

How can I make sure that I am buying livestock products that respect high animal welfare/health standards?

The answer is simple: buy European products whenever possible! Legislation on animal welfare standards for animals is quite wide in Europe and livestock producers are proud of being on a continent with some of the highest welfare standards worldwide for animals, both at farm, at transport and at slaughtering level.

Since the 1980s the EU has put in place regulations to guarantee an acceptable level of animal welfare when it comes to food production in Europe. There are also a high number of initiatives coming from the food supply chain in response to the consumers demands for improved animal welfare. Existing quality labels are for instance integrating new elements in their specifications while animal welfare labels are currently experimenting with the consumer appetite for those products.

But the big question is: how to differentiate animal welfare standards from methods of production when, in the EU, you have always to respect animal welfare in every type of production? And how to manage to present it in the label when it is already mandatory to commercialize any animal product and, as such, you cannot indicate specifically “respecting animal welfare standards” in the label Special Eurobarometer 442, December 2015?

Sources:

- Special Eurobarometer 442, December 2015