Eat Real Food: why is the US flipping the food pyramid?

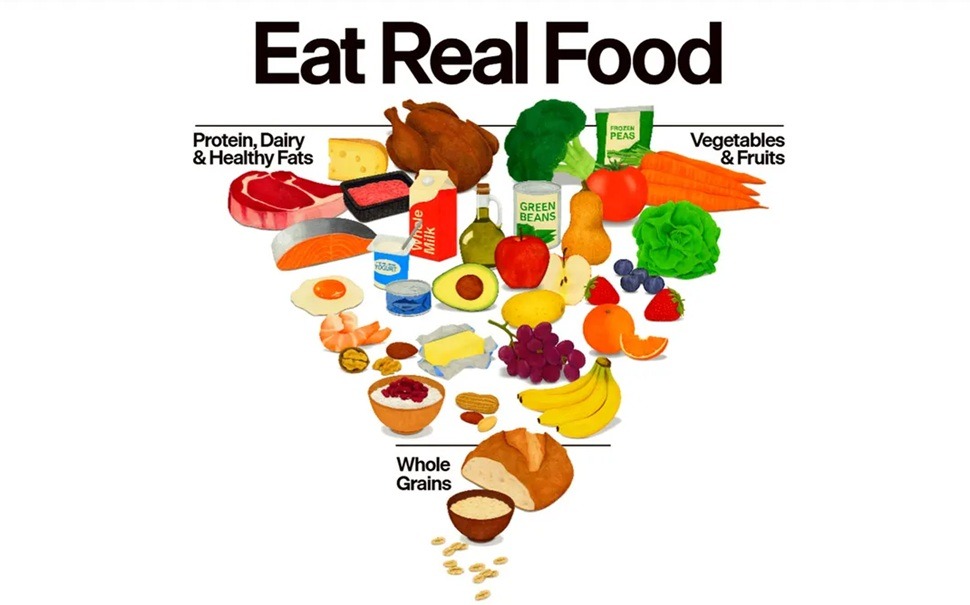

One of the most talked-about topics in food and nutrition circles recently is the new US Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) 2025–2030. With the food pyramid presented in an inverted form, with proteins, including meat, placed at the base and carbohydrates at the top, reversing the structure of previous guidelines. This has sparked a lot of debate among scientists and policymakers working in this domain.

In reality, a closer analysis shows that the inverted pyramid is not an invitation to overturn established dietary hierarchies indiscriminately. Rather, it aims to shift the focus away from the demonisation of individual foods and nutrient-based restrictions, and toward the overall quality of the diet, placing recognisable, natural, and minimally processed foods at the centre. In this respect, the similarities with the Mediterranean Diet are particularly strong.

We took a closer look…

Eat Real Food: the problem isn’t meat, but ultra-processed products

The new guidelines acknowledge that the problem is not meat nor animal fats, but a food system dominated by ultra-processed products, added sugars, refined carbohydrates, sugary drinks, and sweet and salty snacks, which today provide the majority of calories consumed in the US, like other developed countries such as the UK and Australia. A dramatic reduction in highly processed foods is recommended, which, in the American context, characterised by high rates of obesity, diabetes, and overconsumption of calories, represent the main public health challenges.

The message “Eat Real Food” is unequivocal: prioritise real, wholesome, recognisable foods, reducing reliance on industrial ultra-processed substitutes rich in additives. At the base of the inverted pyramid the components considered foundational for a more balanced diet can be found: proteins from various sources, both animal and plant proteins, full-fat dairy rather than “light” versions, healthy fats, and whole foods, accompanied by fruit and vegetables. In this new structure, animal proteins play a central role due to their proven benefits: greater satiety, maintenance of muscle mass, metabolic support, better blood sugar stability, and the prevention of diabetes and obesity.

Saturated fats are no longer “bad,” but “healthy fats”

A significant aspect of the new pyramid is the move away from the explicit demonisation of animal-based foods and saturated fats. Meat, fish, eggs, and dairy, especially full-fat, unsweetened versions, are presented as healthy options within a balanced dietary pattern. Similarly, fats previously considered “problematic,” such as butter and beef tallow, are no longer excluded outright; they are now included among “healthy fats” as wholesome alternatives to be used in moderation and within an overall high-quality diet.

The US Dietary Guidelines thus recognise the importance of rebuilding structured, satisfying meals based on recognisable foods. The presence of animal-based foods and fats echoe characteristics of the Mediterranean Diet, where such foods have always been well represented.

Similar to the Mediterranean Diet, but with important twists

A closer look at the US-recommended portions of meat, fish, eggs, and dairy reveals that they closely match the traditional intake of Mediterranean populations: regular but moderate consumption within a varied diet rich in fruit, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts. So this is not a dietary revolution, but instead a delayed alignment with the long-established Mediterranean model. The inverted food pyramid also signals a shift away from decades of nutrient-focused and restrictive strategies, whose failure is reflected in today’s metabolic crisis in the United States.

Another important change is the increased scientific rigour of the guidelines. For the first time, they clearly distinguish solid experimental evidence from mere statistical associations, finding no strong causal link between consumption of red or processed meat and chronic disease. While the journey is not over, the new direction—focusing on overall dietary patterns and real foods—appears to be a meaningful step forward for a healthier population.

Socio-economic changes and so-called “Westernization” of diets are driving increases in over time in many European countries where packaged snacks, sugary drinks, fast foods, and ready meals are now so readily available. The debates around dietary guidelines will no doubt continue but, reliance of scientific rigour should remain the foundation.